This is the first in a series of posts discussing my research into the history of the 1922 U.S. Supreme Court case of Federal Baseball Club of Baltimore v. National League, culminating in my recently released book, Baseball on Trial: The Origin of Baseball's Antitrust Exemption.

One hundred years ago, professional baseball was in a state of turmoil. The two major leagues, the American and National, were facing a challenge to their supremacy from the rival Federal League. After completing its initial season in 1913 employing mostly semi-professional and former pro players, the Federal League announced its intentions to elevate itself to major league status in 1914 by signing major league players away from their current clubs. The Federal League believed it could do this based on advice from its legal counsel, who had determined that the existing standard major league player contract was legally unenforceable due to two provisions: the reserve clause and the ten-day release provision. The reserve clause assigned each team the automatic right to renew its players' contracts for the following season, effectively tying players to their current teams for the entire length of their careers. Meanwhile, the ten-day release provision allowed teams to release their players for any reason at all simply by providing them with ten days notice.

The Federal League's attorneys believed that these two provisions, taken in combination, rendered the players' contracts legally unenforceable due to a lack of mutuality, insofar as they believed it was unfair to force a player to work for a single team for his entire career when the team itself was bound to the player for no more than ten days at a time. The Federal League's position was supported by several legal decisions arising out of the so-called Players' League challenge of 1890, in which courts refused to enforce the reserve clause in players' contracts. See Metropolitan Exhibition Co. v. Ward, 9 N. Y. Supp. 779 (Sup. Ct. 1890); Metropolitan Exhibition Co. v. Ewing, 42 Fed. 198 (C. C. S. D. N. Y. 1890). Based on this legal theory, the Federal League successfully persuaded approximately 50 major league players to sign with it during the 1913-14 off-season.

The major leagues fought back by aggressively recruiting the defecting players back into their fold, often offering the players significant raises. Ultimately, thirteen different lawsuits were filed between the two sides in 1914, as the parties sought injunctions to prevent their players from jumping back and forth between the leagues. While devoted students of baseball legal history may have already been aware of several of these cases, including Cincinnati Exhibition Co. v. Marsans, 216 F. 269 (E.D. Mo. 1914), Weeghman v. Killefer, 215 F. 168 (W.D. Mich. 1914), and American League Baseball Club of Chicago v. Chase, 149 N.Y.S. 6 (Erie County Sup. Ct. 1914), others had been largely forgotten prior to my research.

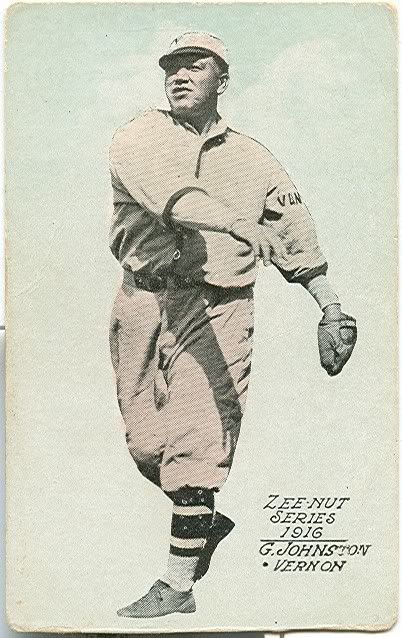

For example, one of the most significant cases of the year involved pitcher George "Chief" Johnson (pictured), who defected to the Federal League in April 1914 following a dispute with his prior team, the Cincinnati Reds. The Reds immediately secured a temporary injunction in Illinois state court to prevent Johnson from making his Federal League debut in Chicago during the inaugural game at Weeghman Park, better known today as Wrigley Field. By the time Cincinnati's attorneys reached the ballpark, however, the game had already begun, so Johnson was served with the court papers when walking off the field after the second inning.

The court eventually held a hearing several weeks later to decide whether to issue a permanent injunction preventing Johnson from playing for his new team. The Federal League was so confident it would ultimately prevail in the Johnson case that it reportedly arranged for as many as thirty-seven major league players to jump to the new league should it receive a favorable decision from the Chicago court. Unfortunately for the Federals, however, the state court judge issued a permanent injunction on June 3, 1914, upholding the standard player contract Johnson had signed with the Reds, on the basis that it must have been fair in light of the number of players who had voluntarily agreed its terms. Although this decision would be overturned on appeal several weeks later -- allowing Johnson to resume his Federal League career -- the damage had been done, as the Federal League's planned raid of the major leagues fell apart following the trial court decision.

While the initial decision by the Johnson court was a significant set-back for the Federal League, the parties ultimately battled to a draw in their 1914 litigation efforts, with both sides winning several important decisions. Perhaps more significantly, these lawsuits also set the stage for the next major phase of the Federal League's legal challenge to the major leagues, namely the federal antitrust lawsuit it filed with Judge Kenesaw Mountain Landis in 1915 (to be discussed in my next post).

No comments:

Post a Comment