This is the sixth and final installment in a series of posts discussing my research into the history of the 1922 U.S. Supreme Court case of Federal Baseball Club of Baltimore v. National League, culminating in my recently released book, Baseball on Trial: The Origin of Baseball's Antitrust Exemption. Click here to read the earlier posts in the series.

Because both the Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia and the U.S. Supreme Court issued published decisions in the Federal Baseball case, most sports law enthusiasts are well aware of how Baltimore's suit against the major leagues ultimately fared on appeal. Nevertheless, I was able to discover several interesting details about both proceedings during the course of my research.

For example, the court of appeals held its oral argument in Baltimore's case less than three weeks after the news that the 1919 World Series had been fixed became public. The impact that the Black Sox scandal would have on the appellate court's decision in the case was undoubtedly a concern for the major leagues. Indeed, some suspected that the court of appeals would conclude that baseball was subject to the Sherman Act because the scandal revealed the need for greater regulation of the sport. On the other hand, it is also possible that the court may have been willing to allow the American and National Leagues greater leeway to collectively centralize their operations in order to impose the type of discipline and authority that the scandal necessitated. Thus, it is ultimately unclear what impact, if any, the Black Sox scandal had on the appellate court's decision in the case.

The court of appeals eventually reversed the trial court and held that professional baseball did not constitute interstate commerce. In particular, the circuit court characterized the major leagues as being engaged in "sport" not "commerce," while stating that Baltimore's case primarily focused on the reserve clause. This latter portion of the opinion has caused some subsequent courts and commentators to believe that the suit only involved allegations concerning the reserve clause, when in reality Baltimore's claims were broader.

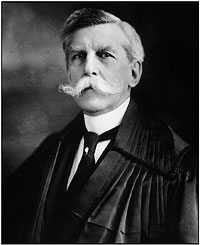

Nevertheless, the Supreme Court ultimately affirmed the court of appeals' decision in 1922. Although the Supreme Court's decision has always been understood to be unanimous, my research revealed that at least two justices -- Brandeis and McKenna -- initially cast dissenting votes. Indeed, both justices eventually wrote to Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr. (pictured), the author of the majority opinion, to report that they were switching their votes so that the decision could be unanimous.

Justice Holmes's opinion in the case has regularly been misinterpreted, with many believing that it simply held that professional baseball was not sufficiently interstate in nature to fall within the Sherman Act. In reality, Holmes' decision was premised on two separate grounds. Most fundamentally, he determined that baseball was not commerce, adopting the major leagues' characterization of the term as being limited to the production or sale of tangible goods. In particular, Holmes stated that "the exhibition, although made for money would not be called trade or commerce in the commonly accepted use of those words." In addition, Holmes also determined that professional baseball was not interstate in nature because the entire source of the industry's revenue -- i.e., ticket sales to baseball exhibitions -- was generated within a single state. The transportation of players across state lines, he concluded, was thus merely "incidental."

While subsequent commentators have been highly critical of Holmes' decision in the case, my research revealed that both parts of his holding were consistent with the legal precedents in place at the time. Moreover, neither of these arguments was ever effectively rebutted by Baltimore's counsel in its briefing. Therefore, my book ultimately concludes that the Federal Baseball case, although heavily criticized today, was in fact correctly decided given the applicable legal precedents in place in 1922.

No comments:

Post a Comment